Travel Logs - Volume 4: Africa 1983

A Trip to Kilimanjaro, Ngorongoro Crater, The Serengeti, and Lake Manyara in Tanzania, with Additional Adventures in Rwanda, Burundi, and Zaire

By Chris B. Allen

Text and Photos copyright © 2013 Chris B. Allen

All Rights Reserved

Dedication

I would like to express my sincere gratitude to my family and friends for their support and encouragement.

I owe a sincere debt of gratitude to my friend Bob for his long friendship – and for being such a resourceful and tolerant travelling companion.

Preface

As an undergraduate at Hampshire College in Amherst, Massachusetts in the early ‘70s, I became friends with a fellow named Bob, who was, by nature, sharp and well informed. Over the past 40 years, we have shared many hikes and adventures (and concerts) in various places. As a matter of course, Bob kept up with the New York Times. At one point, he read an article in the Times describing Kilimanjaro as the highest mountain in the world that you can just walk up. We decided then that we should try to attempt it before we reached our 30th birthdays. As it worked out, I was 29 and Bob was 28 when we embarked on the trip described here.

In 1982, on Christmas Day, we set off for Africa. Bob, who had travelled quite a bit, had never been to Africa. My previous travel experience had mostly been family trips, for which I had been more of a participant than an organizer.

More than any other travel vacation I have taken in my life, this trip truly did unfold spontaneously without an advance script. The constraining structure of our trip consisted, essentially, of plane reservations to and from Tanzania. Beyond that, while we were there, we hoped and expected to attempt to hike Kilimanjaro, visit some game parks, and experience other adventures and attractions as time, money, and geography permitted. Other than the plane to and fro, we had no reservations anyplace.

Aside from his value as an affable travel companion and friend, Bob also brought practical knowledge, wisdom, and experience about such issues as currency exchange, travel dynamics, and logistical planning. Bob knew that often you can change money from one country’s currency to another at a much better exchange rate than the official one that the country involved tries to force on you. Before our trip, Bob bought for us about $1,500-worth of Tanzanian shillings from a (perfectly legitimate) currency dealer in New York – at an exchange rate almost 3 times better than we would obtain in Tanzania. Tanzania and other countries try to prevent such economically practical behavior by requiring paperwork to demonstrate that you have changed sufficient money, at their approved rate, to cover your expenses. We weren’t sure how this would play out, but ultimately our ‘cheap money’ enabled us to afford, particularly, a Kilimanjaro trek and a safari to game parks in Tanzania. These adventures are described in this volume.

The time period reported spans December, 1982 into January, 1983. Conditions and circumstances have undoubtedly changed a great deal since our journey 30 years ago. The horrific Rwandan genocide took place more than 10 years after we visited. Zaire, which had been “The Republic of the Congo”, but was Zaire when we were there, is now the Democratic Republic of the Congo. And it continues to suffer from conflict and adversity that we did not encounter at the time of our travel.

This book is not a travel guide. There is little attention paid here to describing the locations and cultures we encountered. This is a trip journal that reports our activities and adventures as I experienced them. That said, we were fortunate to see many spectacular sights and wildlife. Many of the photos taken during the trip are included to illustrate the chronicle. Some additional photos from the trip are presented at: http://www.reluctantdragon.com/Africa/africa00.htm.

Thanks for reading.

Chris B. Allen

chrisballen@eml.cc

May, 2013

Starting Out - Travel to Kilimanjaro

Safari to Tanzanian Game Parks

Gisenyi to Bukavu – In Search of Gorillas

Bukavu to Bujumbura to Kigoma to Dar es Salaam

Starting Out - Travel to Kilimanjaro

We left on Christmas Day, 1982. A truncated Xmas dinner saw me leaving for Washington, D.C.'s National Airport. A few hours later I met my friend and fellow traveler, Bob, at J.F.K. Airport in New York. Bob's a seasoned world traveller and, as such, has outgrown the need to arrive early for a flight. The cursory half hour before flight time is only for the faint of heart. Unfortunately for me, Bob had my ticket with him, and I spent an interminable interval scanning the travelling hordes for his face.

When he finally did arrive with his family, we were processed and went on with them toward the gate. In 1982, they had not yet imposed ‘passengers only’ restrictions on who could go to the departure gate. Bob had to make good-bye and last-minute-business phone calls to his various womenfriends around the city. His family and I occupied one another's attention near the phone booth as we watched the "Now Boarding" sign flash relentlessly on and off. Finally, Bob and I got on the plane and we were off.

It never happens that one is inadvertently placed in a seat next to an attractive and desirable young woman, but for once I was so blessed. She was only fifteen or so, so the limits were set, but she did occupy much of my attention on the flight, thereby preventing sleep during the overnight flight.

Morning found us in Frankfurt, Germany with 16 hours to kill before our flight southward to Kilimanjaro. We were feeling ambitious. There were some Medieval churches Bob wanted to look at in the neighborhood of the scenic Black Forest. I was enthusiastically lobbying for some of that famous European skiing. We rented a car and set off to play it by ear. I was driving our little Renault on the Autobahn at 115 km/h or so and people were blowing our doors off (so to speak) passing us at probably 150 or 175 km/h. After U.S. driving at constrained rates of speed, it was a different world.

We made it as far as Heidelberg when our exhaustion caught up with us. We found a hotel and paid the surcharge so we could use the shower down the hall, and went to sleep. By the time we woke up and took a shower, we had time only for a brief driving and walking tour of historic Heidelberg and a provincial dinner of Weiner Schnitzel and beer. We decided that since all we'd done all day was sleep, really, we could have gotten a motel room at the airport and saved the car rental.

Two adventures befell us trying to leave Frankfurt. Our apex fare ticket was written round-trip to Dar es Salaam. An apex fare is considerably cheaper than an ordinary round trip ticket, but carries with it certain restrictions. The flights can't be changed, the dates can't be changed, and so forth. We knew in booking the flight that Kilimanjaro Airport was the stop before Dar and thought we could just forfeit the last leg of the flight to Dar. The Frankfurt ticket agent had no problem with that, but when Bob asked if we could get our baggage off the plane there, too, he got all bent out of shape. He admitted that he couldn't keep us on the plane, but balked at sanctifying the breach of regulations by putting Kilimanjaro claim checks on our baggage instead of Dar. Finally, Bob convinced him that it was OK, and we went to write a last batch of postcards home before we entered the Africa zone of unreliable mails.

I carried my film for the trip with me in my hand baggage so as to avoid X-rays. When we got to the checkpoint, the German guard insisted there were no X-rays in his machine, "Film no problem." My film was carefully sealed by Kodak in twenty-roll bricks. It had not been opened. The guard would not look at my film but insisted that I put it in the machine, unless, he conceded, I were to take out each roll of film; out of the brick, out of the box, and out of the plastic cannister. I unpacked about 10 rolls in this way, but it was going to take another month, so finally I relented and put a brick and a half in his little machine. "No X-ray; film no problem!" They were X-rays all right. On the screen I could see 30 tiny spools of film, inside 30 film cartridges, inside 30 plastic cannisters , inside 30 cardboard boxes. Incidentally, the pictures basically turned out fine, but on some of them there is a washed-out appearance; the contrast is reduced, and the underexposed portions of the image which should be truly dark, aren't. Whether the "fogging" of the film occurred before exposure, or after exposure, in a similar forced-X-ray incident in Paris, I don't know.

The second night of our trip was spent like the first, on an airplane. The plane stopped at Karthoum and Addis Ababa, but we were not allowed off. The pilot announced a view of Kilimanjaro and we knew we had finally arrived. We landed at Kilimanjaro International Airport and prepared for our first major hurdle: Customs.

Kilimanjaro International Airport

In many countries around the world, there is a strong black market for goods and currency. In Tanzania this is the case. The government requires that all foreign money be exchanged only at officially designated places and at the official rate, or about 9.5 Tanzanian Shillings to the dollar. On the street, one can get up to 50 or 60 shillings for a dollar. In order to prevent tourists from getting the better exchange rate, the government requires that currency declaration forms be filled out upon entering and leaving the country. Moreover, whenever foreign money is exchanged, the transaction is noted and stamped on the exchange form which must be surrendered when leaving the country. Another complication arises because government-run enterprises such as the national parks and many hotels are instructed to check currency exchange forms and make sure that sufficient money has been legally exchanged to account for transactions. My friend Bob, being the seasoned world traveller that he is, had thought to check in New York to see if any Tanzanian currency was, by chance, available at a more reasonable exchange rate than that the government would give us. He was able to get a rate of about 28 shillings to the dollar, or about 3 times the official rate. He bought about 1,500 dollars'-worth of Tanzanian shillings and thereby relieved us of the danger and anxiety of attempting black market transactions in Tanzania. There was one problem however: we had to get the money into the country. I was willing to split the price of the money, and the loss if we got caught, but if Bob bought the money, he was going to have to carry it in. Tanzania is a poor country, lacking in marketable natural resources and other commercial salvation. The weekly wage, set by the government, was 20 shillings, about 2 dollars at the official rate. Noone had any money, so there was no need for a diversity of currency. The bills only came in denominations of 10, 20, and 50 shillings. The 50 shilling bill was roughly equivalent to a five dollar bill at the official rate or about $1.75 at the rate we got. Needless to say, $1,500.00 in $1.75 bills is quite a wad. The idea of smuggling it through customs was a source of considerable anxiety.

We figured that the government would try to minimize hassles to incoming tourists, since they want our money so badly. Sure enough, the customs officer hardly glanced at our possessions. The illicit wad had been carefully, and with great difficulty, stuffed into a money belt worn inside Bob's clothing. I said "belt", actually it was more like an inner tube. To our relief, it passed customs unnoticed.

We managed to split a cab with other tourists, after considerable haggling with cabbies for a reasonable fare, and went into Moshi, one of the larger cities in northern Tanzania. We walked to the bus parking area and managed to find a bus headed toward Merangu, a village on the southeast flank of Kilimanjaro and the origin of our trek up it. We were the only whites around and attracted considerable attention from the other passengers. Apparently there is limited opportunity for bathing in these regions. There was no shortage of flies. The flies seemed to be attracted both by the bus passengers and the baggage, much of which consisted of bunches of bananas, sacks of grain, live chickens, and so forth. There seemed to be no schedule for the bus. When it was full, it left. Many of the larger pieces of baggage were thrown on the roof and arranged by a couple of fifteen-year-olds who spent much of the bus ride clamoring up on the roof and then back down a ladder into the bus, while the bus was careening along the pothole-riven road.

The Marangu Hotel.

Someone, he looked like just another native passenger to us, came around and collected fares. It was unclear how much he wanted from us and we gave him a hundred shillings. We decided there was no way the bus cost that much and we asked about our change. The fellow would gladly and quietly have kept it (or at least that was our feeling) but he did return later with 70 shillings. There was no animosity in the interaction, but there seemed to be an underlying idea here and elsewhere on our travels, that the whites all have infinite money and will happily give it away if asked or begged, and are to be cheated out of it if they can't protect themselves in commercial transactions. I was amazed and still am, that there wasn't more hostility and resentment about our being (apparently) rich and mobile. We never felt that we were in danger, nor did we ever feel the overt resentment which I certainly would have exhibited if the situations had been reversed. After an hour or so on the bus we disembarked at the Marangu Hotel.

We had read and heard that one could go to the Marangu Hotel and, without prior reservations, sign onto a trek up Kilimanjaro. When we inquired, we were told that we could go up the mountain two days hence, and we could camp out on the grounds of the hotel for the night, there would be no vacancy until tomorrow. That all sounded pretty good to us. We pitched our little pup tent and managed to find a small cement hut with a shower in it, consisting of water diverted from the little stream which ran beside it. The ambient water temperature was probably about 70; it felt very refreshing. Later on, we moseyed over to the dining room and discovered the local beer, Safari Lager, in (big) 700ml bottles, 22 shillings (about $2.30 at the official rate.) There was only one dinner, which everyone ate: soup and meat and potatoes and vegetables. A platter would be set on the table and we would help ourselves, then the platter would be moved to another table, and so on. The management of the hotel was British and the meals were overall bland, but wholesome. Breakfast consisted of porridge and meat, eggs, and toast. It didn't take many meals before we'd picked up the mild case of diarrhea which we maintained throughout the trip. When travelling in Africa, Lomotil (diarrhea-control medicine) is an absolute necessity. Also, one should bring one's own toilet paper. While we were there, a severe toilet paper shortage was in progress. Even the tourist hotels, which are ordinarily the last to run out (we were told) were in short to nonexistent supply.

The perennial afternoon cloudiness dissipated in the evening, and we got our first glimpse (since we'd landed) of Kibo, the summit peak of Kilimanjaro.

View of Kibo from the Marangu Hotel.

The next morning, we decided to go for a scenic first stroll in Africa. No sooner had we walked outside the gate of the hotel, than we were accosted by a quiet friendly local who spoke fairly good English. He showed us where there was a waterfall, and then took us to the local cooperative store. There were only 40 or 50 different items for sale there, including two types of wine, one or two types of crackers, one kind of cookies: ginger snaps. It was a pretty sparse offering. At the rate of pay we'd heard the natives make (20 shillings/week) it was three or four day's pay for a box of crackers. We found it rather sobering. Our guide walked us back to the Marangu by a back way, past cement and wood huts and coffee trees and banana trees and men, women, and children (down to very small) carrying bundles of bananas or sacks of grain toward home or market. Everyone compulsively, said "Jambo!" as we passed. We Jambo'd back. Some of the little kids, particularly, seemed to think that if they were friendly to us in that way, that we would reward them with a tip. When it didn't work, some of them would try it again; they'd run after us and smile and say again, more insistently,"Jambo!"

When we got back to the hotel we gave our guide 40 shillings. We found it a problem trying to figure out how much was appropriate. One doesn't want to be insulting, one wants to be fair, one doesn't want to be exorbitantly gracious...

Hiking Kilimanjaro

The next day we got organized to hike up the big mountain. In the morning someone came around to ask if we needed anything. The hotel has a miscellaneous assortment of hiking and camping gear which they are willing to loan to Kilimanjaro climbers. Neither Bob nor myself had any headgear to protect from the relentless equatorial sun, so we borrowed some corny sunhats with "Marangu Hotel" embroidered askew across the brim. We were pleased to be otherwise adequately equipped, because most of the loaner gear had long since seen better days.

Ten other people had signed up to leave the same day, so we were all assembled together for a lecture by the owner of the Marangu Hotel, Mrs. von Lany. She explained that it was important to go slowly so that the body can become gradually used to the lack of oxygen one finds at high altitude. She told us what our schedule was: Mandara Hut the first night, Horombo Hut the second, Kibo Hut the third, but then up at 1 a.m. for the bid for the summit, then a long day's hike all the way back to Horombo Hut for the fourth night, then back out to the Marangu Hotel on the fifth day. She seemed to be about 70 and had an imposing air of authority about her. I've since read that she's been up the mountain to the summit a number of times (I can't remember which number!) and was not impressed by Hemingway, apparently saying about him, "He never got close to the summit." I was seized with goose bumps as she was talking, suddenly sensing that I was on the verge of something whose magnitude I wasn't exactly sure of, but it was big.

After our pep talk, we went outside to meet our porters and guides. For the twelve hikers, there were 17 porters, 3 assistant guides, and 1 head guide. Some of the porters were to carry gear for the other porters and guides, as well as food for the party. And each of us had one porter to carry our gear as well as whatever food and dishes could be crammed into the burlap sack which each porter would carry on his head. Some of the porters couldn't have been more than ten or twelve years old, and one could see their dismay as they tested the heft of the torture they were to bear. There was little conversation beyond a handshake and name exchange, before we piled into vehicles to get ferried up to the gate of the park.

Entering Kilimanjaro National Park.

At the park gate, we registered at a modern A-frame chalet of creosoted wood with a galvanized corrugated roof. That building typified the architectural motif of Kilimanjaro. It is now required that anyone attempting to climb the mountain do so under supervision of a registered guide. I guess there were too many events like one I read about: some climbers came upon the body of someone near the summit, who'd frozen to death and still remained in position as if he was about to eat an orange. We had to write down passport numbers, and who was our guide, and who was to be notified, just in case... It was about 2 o'clock when we got to the gate. After registering we all sat down to eat box lunches.

We Set Out Through the Jungle.

At about 2:30, we set off on the well-trodden jeep road through dense leafy jungle. Surprisingly there wasn't much evidence of animal life. We saw a few birds. Occasionally, a shy monkey would cackle at us and rustle some branches, otherwise remaining invisible. Unlike the jungle movie scenario, we were not in a long safari line with the natives all singing. The porters had taken off with our gear while we ate our box lunches. The guides were ahead of us, or behind with other members of our party, or making things ready for us at the hut up ahead. We were walking along in groups of two or three as our sociability dictated. We hiked up the main tourist route and there was no ambiguity about which way to go. Occasionally, we would come across a sign, e.g. "Mandara Hut, 2 mi." It didn't seem much like darkest Africa at all; except for the vegetation, it could have been a trail in some U.S. park. Another reminder of our true location was furnished by the stream of porters and occasionally tourists, mostly European, coming down the trail toward us. Everyone dutifully said, "Jambo", as they passed, even the tourists, who were indoctrinated fully after four or five days on the mountain. On the mountain, passing hordes of porters and guides we learned the usefulness of a few important Swahili phrases: Jambo - hello, Habari - how are you, Polee Polee - slowly, slowly, and Homna Tabu - there is no problem. A variant of this latter phrase became particularly useful later on: Homna petrol - there is no gasoline.

Mandara Hut.

After about 3 hours of pleasant hiking, we arrived at Mandara Hut. This was a modern-looking A-frame building similar to that at the park gate. I'd read horror stories about tiny uncomfortable, overcrowded huts laden with vomit from altitude-sick tourists, so I was pleasantly surprised by the truth. There were bunks in the upper level with 3 -inch foam rubber mattresses. There were openable windows lending a refreshing breeze. There were a couple of picnic tables outside on the porch and some other hikers were sitting around. There was a group of 4 Europeans on vacation from Rwanda (which Bob and I would visit later on in our trip). After a while, my porter showed up with my gear and I was able to put on some long pants and a sweater and contemplate my surroundings. Mandara Hut, altitude 9,000 feet, 6:15 p.m., temperature 54 degrees F., scenic, albeit hazy, views of Moshi and Marangu to the south, as well as isolated chains of cinder cones, gentle breeze, sunset colors beginning to appear as clouds began to dissipate overhead.

Other members of our Merangu Hotel party appeared gradually in clumps of two and three. It got dark and still two members of our party had not arrived. Those of us who had arrived had a chance to get acquainted while we waited for the tardy trekkers and for dinner. The missing members of our party were Eric and his father. Eric and his wife Eve were Americans living in Dar es Salaam for three years while Eric acted as agricultural consultant to the Tanzanian government. He was trying to install a new cash crop to the Tanzanian economy. The jojoba bean is the source of an industrially useful oil and thrives in an Arizona climate and soil which are apparently virtually identical to the climate and soil of Tanzania. Eric's parents were visiting from New Hampshire and were getting the grand tour of Tanzania, including Kilimanjaro. They were planning to hike as far as the second hut and then have a leisurely walk back down. As it turned out, the reason for the delay was that Eric's father was not as healthy as he thought, and the hike to 9,000 feet was almost more than he could take. While we were sitting happily at Mandara Hut wondering what was going on, Eric's father was vomiting and having a miserable time. Eric was with him trying to be helpful and supportive. Their already slow progress was further hampered by the onset of darkness. Eric's mother and his wife, Eve, had arrived earlier at the hut, not having had any problems. One of the porters was sent back down the trail with warm sweaters and a flashlight.

We decided not to wait any longer before starting dinner, vowing to save some for our hapless friends. Dinner in the wild proved to be virtually identical to the civilized Merangu Hotel dinner we'd become used to. Soup was followed by a vegetable and meat course, with potatoes, noodles, or rice. There was some sliced bread and margarine and some kind of jelly. This feast was all served in the grand style by the guides and a few of the porters. The feast was set on a linen tablecloth stretched along two picnic tables placed end-to-end inside the hut. We each had a cloth napkin, whose identity was personalized by an embroidered number. None of the place settings were matched, one would have been hard-pressed to find two matching utensils at all; one must be dedicated to the idea of roughing it if one is to climb Kilimanjaro!

Eric and his father finally arrived at about 9 o'clock. Eric's father went straight to bed and felt much better in the morning. He and Eric's mother spent the day around Mandara Hut and then walked back down.

In the morning after breakfast we ambled off in groups of two and three as we were ready. The transition from dense jungle to more open, semi-arid grassland had occurred just below Mandara Hut and we now walked through grassland. It was very pleasant going, perhaps 70 to 75 degrees, with a light breeze. The sun was gradually obscured by clouds and we didn't see it from about noon to just before sunset.

We Left the Jungle. After Mandara Hut We Traversed Scrubby Grassland.

The vegetation became scrubbier and scrubbier as the day progressed and became more and more desertlike. Wisps of cloud were blowing past and contributed to a feeling of otherworldliness. About a half hour before Horombo hut, at about 2:15, the clouds let loose a torrential downpour. An accelerated pace brought us to the hut well ahead of our porters and our dry clothing. It was 47 degrees F. and a fairly stiff wind was blowing, altitude 12,340 ft.

Horombo Hut with Cloud-Draped Mawenzi in the Background.

A few hours later, the clouds disappeared entirely, except over Kibo, where they lingered into the night. Behind the hut, the older and more dissected, jagged peak of Mawenzi loomed imposingly. Horombo Hut isn't much, if any, bigger than Mandara Hut, but it's the only hut on the route where people spend two nights, both going up and coming down. It turned out that there wasn't space for us in the main hut, so we were given one of the porters' huts. These were smaller, one-story A-frame structures, with skinnier bunks but, surprisingly, also foam rubber mattresses. I say "surprisingly" because the porters' life does not seem to be one very filled with comforts of any type. These people seemed in general to be underclad, undershod, underpaid, and overloaded. They are also underbathed, and I was pleased to find an absence of vermin in their quarters.

Kibo Was Visible Over Horombo Hut A-Frames.

At Mandara Hut, we'd been surprised to find flush toilets. Here at Horombo Hut there were separate men's and ladies' A-frame outhouses, discreetly placed at a difficult distance for the diarrheaic. There was no seat, just a hole in the cement floor with two raised cement rectangles on each side on which to stoop.

The next morning, the third day, we set out after our usual Merangu-Hotel-on-the-trail breakfast. We began to feel the altitude now as a diminution of stamina; if one attempted a typical low-altitude pace, one would quickly get winded. With a pace reduced by about a third, however, progress was not impeded. After a couple of hours, we reached the "last water" spot. It was quite a social scene, everyone on their way up or down stops here to water-up and chat. As can be seen from the photograph, it's quite a distance that must be traversed, round trip, before returning to drinking water.

Last Water.

Not long after leaving the last watering hole, we reached the saddle. This is a broad ridge connecting Kibo and Mawenzi. There is little inclination and one walks across the saddle for several hours. There is practically no vegetation, except for sparse tufts of hardy grass here and there. While we crossed the saddle, we were often in the clouds, and much of the afternoon it was drizzling or snowing on us. There seemed to be no shortage of moisture to justify the surreal moonlike deadness of the landscape. The scene did not correspond to our image of equatorial Africa.

Walking Across the Saddle.

A half-mile or so below the final hut, Kibo Hut, one leaves the broad, flat saddle and ascends rather steeply to the hut. The pitch would have been trivial ordinarily, but was extremely gruelling at this altitude. I found that after every eight steps I had to stop and breathe heavily. It was strange to discover a distinction between being tired and being winded. I wasn't tired, but I had to stop and rest, all the muscles hurt from lack of oxygen, even though the exertion hadn't been that strenuous.

Kibo Hut.

Kibo Hut, 15,520 ft., is not an A-frame but a normal style building of rocks and mortar and wood. It did have the expected corrugated tin roof, however. I arrived at the hut and sat down to bring my annals up to date. After 3 sentences, I was sick. I staggered outside toward the outhouse and threw up on the nearest rock. After a while, I regained sufficient composure to stagger back inside. This cycle repeated itself several times. I felt as though I had the worst hangover I'd ever had multiplied by a factor of 5 or so. It was awful. Perhaps I had gone too quickly over the course of the day, and the altitude caught up with me. I presume that's the case. I was the only one of our group so affected at this point. Of course I passed on the soup and tea dinner which was our high-altitude meal that night. I was in discomfort both physically and from the thought that I was going to have to return to the world and admit that I never got any higher than the last hut. What a wimp. I recalled people saying that altitude sickness can strike anyone without regard to sex, creed, color, age, state of health, etc., but it didn't help my wounded ego.

I guess I managed to get some sleep, because I remember being awakened along with everyone else at 1 a.m. for the final pitch to the summit. I didn't actually feel that bad at that point, and decided I might as well set out with everyone and go as far as I could. Then, at least, I would know I'd tried for the peak instead of getting beaten at the hut. One of the three Rwandese miners was too sick to go on, so he stayed in bed and went down later that morning. The universally prescribed cure for altitude sickness is lower altitude. Medical attention is apparently rarely required. High altitude pulmonary edema can be very serious and life-threatening, but reportedly it is a relatively rare concomitant of the altitude sickness that afflicts many/most people. Most of the members of our party had headaches of varying severity and intermittency. I was surprised that I never did get much of a headache, even when my friend, Bob, was experiencing his head split apart by the throbbing.

We set out at 2 a.m. The previous distance covered had been of fairly low inclination but long horizontal distance. Now the situation was reversed. The remainder of the hike was consistently steep, ranging I would guess, from 20 to 40 degrees inclination. It was middle of the night, but it was only two or three days past the full moon. The moon had risen at about 10 and the almost-full disk was nearly vertical above us. There was no vegetation to shade the trail so our route was brightly lit. When we started I was able to take 5 to 8 half-paces before pausing to breathe.

The progress was excruciatingly slow. We'd come upon a section of trail and then an hour later we'd still be on it, inching forward almost imperceptibly. The distance we still had to go didn't seem to be shrinking at all. We'd heard tell of this phenomenon. We'd also heard that when we got to the highest point we could see, from there we would see another above us and another, endlessly.

At 6 a.m. we stopped for tea at Tanzia Cave. I was no worse off than anyone else healthwise. In fact, I was perhaps the only person without a terrible headache. I was not very motivated at this point to take pictures, being much too preoccupied with the agonizing exertion which never seemed to end. But, I did manage to snap off one shot from the cave, of sunrise over Mawenzi.

Sunrise over Mawenzi.

The sun came up and found us entering the zone of snowfields. A foot or so of snow covered the scree slope, and the trail zigzagged up forever. The clouds hadn't set in yet, because of the early hour, and we were glad we'd brought our glacier goggles (basically these are extra-dark sunglasses).

Ten or twelve people passed us; they were on their way down. They had left the hut (apparently, I never heard them) before we did for their ascent. A couple had made it to the true summit, Uhuru Peak. It was encouraging to hear this, because the general consensus at the huts had been that the snow conditions on top precluded passage to Uhuru.

This portion of the hike was the hardest piece of physical exertion I've ever undertaken. I talked it over later with Bob and we both thought that if one of us had said, "Let's give it up." at that point, we would have. In my own mind I was thinking, "I'm not in pain yet, I'll go on til I have to stop."

Not to my credit, I was bringing up the tail of our caravan for much of this pitch. It was rather interesting to note that Eric's wife, Eve, was in the lead for most of it. Contrary to what we expected, the highest point we could see, that we were plodding agonizingly toward, was not the first of many. When we got to it, we could see Gillman's Point, not far above us. I got my fourteenth wind and raced toward it. Left, right, left, then breathe for a while, left, right, left, breathe, and so on. I was the second member of our party to Gillman's Point. Elation swept over me, I had done it! 18,765 feet, Mount Kilimanjaro, 9:35 a.m., New Year's Day, 1983.

Gillman's Point. Elevation 18,765 feet.

I was so pleased with myself, I felt like I could do anything. Suddenly, I realized that I was getting cold. An hour or so before I had finally let myself be talked out of carrying my daypack. It wasn't very heavy at that point: camera, no extra lenses, a water bottle, a sweater and light windbreaker, that was it. One of the assistant guides, trying to lighten our loads, to relieve some of our agony, had taken on many of our accessory items. Amazingly, he hardly seemed to be impaired by the load. When I reached Gillman's Point, he was still behind with the slower members of our party. It was 37 degrees (F.) and there was a moderate breeze. I lay down in the sun, on a rock that was somewhat sheltered from the wind. The next person up was Lars, the Dane. He said something to the effect of, "Hello, so this is it!" and threw up. The rest of our party trickled in slowly, including the guide with my sweater and jacket, and we all lay down and sat for a while, happy to be alive and proud of our accomplishments. The clouds were thickening around us; Mawenzi, which had been fairly clear when we arrived, was rapidly becoming obscured.

Looking toward Uhuru Peak from Gillman's Point.

I'll never know why the topic of going on to the true summit, Uhuru Peak, never came up. I think that if someone had suggested it, I would have gone for it; I felt perfect after 15 or 20 minutes of breathing and not moving. But noone thought of it, or mentioned it, and for some reason I'll never understand, I didn't either. Perhaps the guides would have said, "No, it's too late in the day, you'll never see anything from the summit because of the clouds, and you won't have time to make it all the way to Horombo Hut."

Our Guide, Menase, at Gillman's Point.

In any case, we started down. By now we were engulfed in the clouds and it was snowing on us. Many of the snowfields we'd zigzagged up were perfect for glissading down. (Glissading is skiing without skis, on one's shoes.) To my frustration, the exertion of controlling one's ballistics while sliding down the snow slope, required constant interruption for heavy breathing. Still, the slide/hike down was ecstasy compared to the torture of the ascent, and we got back to Kibo Hut around 12:30. Everyone sacked out for an hour or so to rest. The guides came in with some kind of fruit drink; it was divine nectar to us. Eric and Eve had staggered in last, and it was evident that Eric was in a bad way. He seemed to be only semi-conscious, responding to diagnostic questions only when they were strenuously delivered. The guide, Menase, fetched the hutkeeper. Eve and many of the rest of us thought that Eric should stay at Kibo Hut for the afternoon and night, resting to regain his strength. The hutkeeper adamantly maintained that if someone was too sick to move themselves, they must be stretchered down to the next hut. The stretcher, stashed outside, was basically a cot with one wheel under the middle of it and four handles, one for each of four porters, at the corners. It seemed to us that getting stretchered was tantamount to being jostled to death, and we were convinced that Eric was suffering from extreme fatigue, for which the proper cure was rest, not movement. In spite of the apparent inviolability of the policy, the hutkeeper relented and agreed that Eric could stay at Kibo Hut. Eve stayed with him. At about 3:00, the rest of us left for Horombo Hut.

Afternoon Clouds Overtake Mawenzi.

Soon we were walking across the saddle, the broad, flat, lifeless desert. This was bliss. Life was perfect. The hike was effortless, painless, in spite of the fact that we'd been working hard physically, most of the time, since 2 a.m. By 5:45, we got to Horombo Hut. It was again too crowded for us to find space in the main hut, but this time, instead of getting a porters' hut, we were given two halves of an auxiliary camper's hut (each half slept four people.) When the porters served us dinner we ate voraciously. No one had eaten much dinner or 1 a.m. breakfast at Kibo Hut the night before; lunch had been just a snack, and we'd been hiking since before dawn. We all slept like proverbial rocks. The next morning, before breakfast, I headed back up the trail for a half mile or so, in hopes of getting some pictures of Kibo, and our route up it, in the clear early morning sunshine. I met Eric and Eve, and our guide, Menase, at about 7:45. They'd just hiked from Kibo Hut, having left there at 5 a.m. Eric was feeling O.K., he seemed to have recovered completely from his overexhaustion of the previous day. This was good, because the day's itinerary included hiking to Mandara Hut and then down to the park gate. This was a stint that had taken two days on the way up. So Eric and Eve, because they'd stayed at Kibo Hut, enjoyed the dubious pleasure of traversing three-day's-worth of mountain in one day. We hiked the half mile or so down to Horombo Hut and had breakfast. During the meal we conferred and computed tips for our one guide, three assistant guides, and seventeen porters. Bob had thought to check with Mrs. von Lany, the owner/manager of the Merangu Hotel, about what were reasonable tips for these people for the four-and-a-half day trek. Even though we multiplied her suggestions by 1.3 to 1.5, the share for each of the ten of us to pay was 260 shillings, or about $27.00 at the official rate.

After breakfast at Horombo Hut, we walked down through increasingly lush vegetation into the grassland above Mandara Hut. Lunch found us at the hut. Then we hiked down through jungle to the park gate where some of us bought "I Climbed Mt. Kilimanjaro in Tanzania, Did You?" t-shirts. We posed for the obligatory group photo, before catching a ride down to the Merangu Hotel.

Our Intrepid Trekking Group.

We were delighted to guzzle our celebratory beer and were interrupted by our main guide Menase, who had arrived with our "climber's certificates". These were pieces of coated paper, signed by our guide and the park warden, proclaiming that we had successfully climbed Kilimanjaro to Gillman's Point, elevation 5,685 m. Eric's parents, who we'd left at Mandara Hut on the second day, were at the hotel and joined in our celebration.

It turned out that Eric and Eve were planning to show Eric’s parents some of the Tanzanian game parks. They were going to be accompanied, in another car, by Roger and Dick. There was room for us to ride with Roger and Dick as far as Arusha. So we left with them after a good night's sleep.

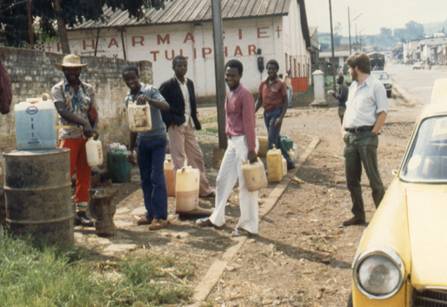

Northern Tanzania Scenery.

We discovered at this point that gasoline was in short supply in Tanzania. Dick had 5/8 of a tank when we started looking for gas en route to Arusha. Several places we stopped had no gas at all. Finally we passed a gas pump which had about 20 people standing around it with one- to five-gallon gas vessels. Someone was pumping a lever on the side of the pump to dispense the gasoline. Metering of quantity seemed to be either by rough guess or number of pumpings. We pulled up as close to the pump as we could get without hitting anyone and waited for our turn. People seemed to be arriving faster than cans were getting filled, and it was obvious that our primacy was being eroded. Dick was a rather timid sort of fellow and remained passive in his assertion. Finally, a good natured local decided it was bad manners to ignore us whites and he saw to it that we got our gas. A couple of other whites drove up and managed to get their gas ahead of us, so it became clear that assertiveness was a key factor. If the fellow hadn't helped us, my feeling was that we might have been there for days (or until the pump ran dry). The funny part of it was that we had plenty of gas to get to Arusha, and if there was gas anywhere there would be some in Arusha. In fact, there was gas in Arusha, but long gas lines. Eric queued in one for a couple of hours before being told that the station was closed until morning. I guess maybe Dick wasn't such a dink after all.

Safari to Tanzanian Game Parks

We checked into the New Arusha Hotel and joined Dick and Roger for lunch there. Then we walked the streets of Arusha in search of an agency that would arrange a safari for us. We talked to seven or eight, perhaps before finding one, Bushtrekker Safaris in our hotel, who could offer us the kind of flexibility of itinerary, immediateness of departure, and apparent casualness about our ‘black market’ money that we were looking for. We knew it would be touch-and-go about the last item until we actually paid and saw whether they were going to require our currency exchange forms. When, in fact, we did pay them, the next morning, not a word was said about it. If they'd required our forms, we would have had to cancel the arrangement. We couldn't afford the safari at official exchange rates. Besides, if we didn't spend that big hunk of our Tanzanian money on a safari, what would we spend it on? It worked out fine. Bushtrekker took our cheaper black market money, and the 5 day, all-expenses-paid safari including park fees, food, and lodging, vehicle and driver, ended up costing us about $400 each, instead of the $1000 it would have cost us at the official rate.

Before we left Arusha on our safari to the game parks, we went to the airline office and bought tickets to fly to Kigali, Rwanda upon our return in 5 days time. The air service is crowded and often unreliable, so it was strongly urged that we buy our tickets in advance. We found that African airlines require foreigners to pay for their tickets in their foreign currency. They didn't mind my American traveler's checks.

So, on the afternoon of January 4, we left Arusha in our Land Rover with our driver, Jonas, bound for Tanzanian game parks. There were a couple of 5-gallon gasoline cans in the back, full, just in case…

We drove across the Masai steppe. Grasslands stretched from the road in all directions. Thatched huts could be seen and flocks of cattle. Cultivated groves of trees and fields were visible here and there. January is between the short rains and the long rains in Tanzania, and things were starting to look rather parched. The country we were driving through was flat to rolling, but dotted here and there with volcanic cinder cones reminding us that this area is geologically active.

Headed West, We Could See the Rift Wall in the Distance.

Headed west, after a couple of hours we approached one of the great rift walls of eastern Africa. The East African rift system represents a zone of action in the earth's crust. It's a zone of stretching and movement which may eventually result, in hundreds of thousands to millions of years, in the formation of an ocean where Lakes Tanganyika and Rudolf, among others, exist today. The fault system splays and branches. In the lake zone I mentioned, a central block bounded by two faults is downdropped, forming the valley filled by the lakes. Other faults in the system are not so neatly grouped in pairs. We drove west toward a two-thousand-foot scarp of one of these unpaired faults. Lake Manyara, the site of one of the three national parks we were to visit is nestled at the base of this fault scarp. We drove toward the imposing wall and then zigzagged our way up it on the road. We passed the Lake Manyara Hotel which guards the crest of the scarp, overlooking the park. We would return to visit Lake Manyara and the park, and the hotel, after we went to Ngorongoro and the Serengeti.

Looking South Along the Rift Scarp, Lake Manyara, to Which We Would Return Later, Is on the Left.

Another couple of hours of driving through more and more rugged topography brought us to the entrance to Ngorongoro Crater National Park. Here, our driver got out and went to show papers to the man in the guardhouse. After a few minutes, Jonas, the driver, emerged, and motioned for Bob and me to go inside. The guard inside asked to see our currency exchange forms. I'd exchanged all of $300 so far and the guard definitely did not think that was enough. He kept saying, "Is that all?" I acted like I didn't know what the problem was. Finally he grumbled and stamped our papers and let us go. We were rather alarmed at the thought of being interrogated at every park entrance and at the hotels. One of these times, we thought, they won't just grumble and let us pass, they'll do something. As it turned out this was the only place on our safari we got hassled. Jonas just gave our vouchers to the hotels and other parks and we weren't detained. We did have to show our currency exchange forms a couple of times but they just wrote down the number and didn't question how much money we had changed.

Ngorongoro Crater

Soon after leaving the park entrance station, we got to a viewpoint. Ngorongoro Crater was spread in a panorama before us. From a point on the rim, we were looking down into the 10- by 12-mile crater. Ahead of us, at our level, were cloud bottoms from which were falling streamers of rain to the crater floor 1500 feet below.

Overlooking Ngorongoro Crater.

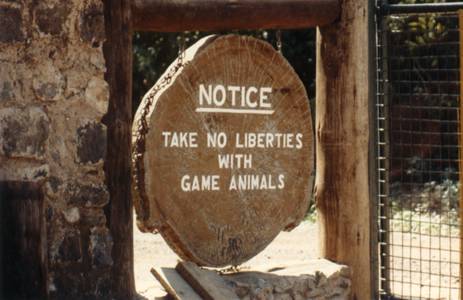

The crater is a closed bowl, with steeply dipping, sloping walls. A plaque at our viewpoint, like others we saw along the rim road, was dedicated to the memory of one of the naturalists who'd been shot by game poachers in the crater. Ignoring poachers, the animal life in the crater inhabits a closed system; animals neither enter nor leave the crater. As we were to see the next day, this makes for a high concentration of furry friends and photogenic fauna.

Driving from the viewpoint to the Ngorongoro Crater Lodge where we were to spend the night, we were surprised to spot Eric and Eve and Roger and Dick driving in the opposite direction. We stopped and said, "Hi." It felt very strange to see people we knew in a continent this size.

Matching Zebras.

At the lodge, we entered the dining room and were shown to a table for four. There were no smaller tables. Soon a couple was seated with us who we'd happened to see in Arusha at a travel agency. They had been trying to arrange airline reservations to Madagascar or something, but here they were at Ngorongoro. A few minutes later, a group of people, Europeans living in Rwanda, who'd beat us to the huts and to the summit of Kilimanjaro by a few hours were seated at the next table over. Small world.

The menu consisted of two choices, we chose the "Roast Leg of Wildebeest". It must have been an old wildebeest; it was tough and stringy, but otherwise could have passed for lamb. After dinner we sat around for a while in the lounge. There was no beer here, so I drank a horrendous concoction of orange squash with kenyagi; this was a mixture of syrupy-sweet orange drink with anise-flavored liqueur. The ice in the glass helped quite a bit. As in most of the game-lodge/tourist hotels we visited, the lounge and dining room walls were thickly layered with dramatic wildlife photographs and stuffed animal heads. We were wondering if any of these National-Geographic-type animal scenes were in store for us.

Wildebeest.

The next morning dawned clear and sparkly. We awoke to a picture window view of the crater bottom from our room. Fog lingered over parts of the flat crater floor. The view was so idyllic and tranquil that it was hard to believe the scene was teeming with animal life and the ongoing struggle for survival.

Ostriches.

After breakfast we drove to pick up an Official Ngorongoro Crater Guide. Once he was in the Land Rover, we drove to the narrow tortuous, steep, no-guard-rail road down into the crater. Just before we got to the crater floor, the parade of wildlife began. There was a huge bird, like a big eagle, in a tree just off the road. Then we started to see gazelles, and wildebeest, and zebras. Later, we got so used to seeing these guys that it got passé, but at first, even they were exciting. Within the first five or ten minutes on the crater floor we spotted also a jackal, and a hyena. Then we saw our first lions. Another Land Rover had already spotted them and was stopped taking pictures. We drove over, too, and did the same. This was a big thrill, LIONS! The lions weren't nearly so thrilled about us; they seemed to be sleepy and bored. Often the lions were quite close to the Land Rovers. Sometimes to encourage their attention, one of us would open the door a crack, then the lions would perk up. Upon closing the door again, the lion would go back to sleep. I think if one of us had actually set foot out of the vehicle, we would have found out that those big soft furry cats were also dangerous, vicious, nasty beasts.

Lion Yawning.

Mother Lion and Cub.

We drove around the crater floor, usually on jeep tracks, but sometimes casting off across the grasslands finding our own route. Jonas, our driver, and the guide had their eyes peeled for animal life. We drove to the crest of a hill and got out to stretch our legs, overlooking the scenic crater floor and walls. In all regions of our view could be seen the herds of wildebeest, zebra, and gazelles we came to know as ubiquitous. We were happy; all these animals, already, and this was only our first full day of game parks! This was the life! It was about 80 degrees out and the air was fairly dry, there was a nice breeze. It can be very pleasant in equatorial Africa at altitudes like these, maybe 8,000 or 9,000 feet.

Bookends.

We were pleased to run across a family of three rhinoceri. Apparently they're irrascible and don't see well, so Jonas wouldn't get very close to them, lest they charge us and overturn or otherwise insult our vehicle.

Rhinoceri.

For lunch we went to a traditional Ngorongoro Crater lunch spot. It's an open pool in a stream course, surrounded by reeds, and sporting a number of bathing hippos. We broke out our box lunches from the hotel and sat by the pool, under a shady tree, and contemplated the hippos. I was munching on a joint of "Roast Leg of Wildebeest" sitting on a rock. I was between bites when I was suddenly aware that my joint of wildebeest was no longer situated in my hand. One of the big hungry-looking birds, which had been circling above us, had dive-bombed and jive-raided my food from my hand. I didn't even feel it. I was lucky; if he'd missed, I probably would have gotten a bloody painful handful of sharp claws. As it was, I didn't have to struggle any more with the gristle-laden carnivosity that I’d been attempting to eat. I managed to sate myself on the remaining sandwich, apple, and miniature, semi-local banana, which I ate in a much more guarded posture, lest the birds get further ideas.

The Lunch Spot.

This Bird Snatched My Lunch.

The hippos didn't do much at this site. Every now and then one of them would open their mouth, we would all yell, "mouth" and snap shutters wildly. Every now and then, one of them would open REAL wide, and we'd get "big mouth". There was a baby hippo floating around with its mother that did add interest to a scene which otherwise got boring fairly quickly. Soon we set off again in search of more animal life.

Mouth.

Big Mouth.

I was shooting pictures with a 100 to 300 mm zoom lens. I was glad I had the long focal length and would not repeat the trip without it. I would even have gone to 400 mm if I could have. Most of the pictures were taken while I stood in the back of the Land Rover with my head and shoulders exposed above the top of the vehicle. The camera was mounted on a 3 foot collapsible tripod which was collapsed and being used essentially as a monopod. Thus I could aim the camera freely but it was more stable than if I'd been holding it with the long lens freehand. Most of my pictures were shot at a 250th at F5.6 or F8. In particularly bright areas I shot at a 500th at F5.6 or F8. I shot the whole trip on Ektachrome 200. I was pleasantly surprised at how warm the color balance was on the pictures and would probably use it again. But even at ASA 200, which is relatively fast, the long lens required such high shutter speeds that I had frustratingly little depth of field. The most exasperating thing came when I discovered after the trip, that my lens was not exactly adjusted to the camera mechanism. I overexposed a whole lot of my pictures when I set the lens to the F-stop prescribed by my built in light meter. One should always know one's equipment when embarking on a trip of this magnitude or irreplacability. I certainly would have used the extra light for depth of field or faster shutter speed, rather than for overexposing the film, if I'd only known... The pictures that suffered the most were my life-and-death African action series which took place at this point in the trip. Fortunately, a bit of gamma correction helped the photos…

We were driving along and drove past a hyena, he was lying on the ground and appeared to be waking from a nap, as we passed I took a picture of him and then he was aroused fully and went trotting off in a direction we were already driving rapidly. Jonas and the guide had seen action up ahead and we were approaching to investigate. I was snapping pictures (overexposed) as soon as I realized what was happening. A group of jackals had surrounded a family of three gazelles, the jackals managed to bring down the baby gazelle. At this point, the hyena we'd just passed came running by and stole the baby gazelle from the jackals and went loping off to eat its newly-stolen lunch.

Hyena Notices Activity.

Jackals Capture a Baby Gazelle.

The Hyena Steals the Gazelle from the Jackals.

Lunchtime for the Hyena.

We came across grandaddy elephant walking alone near the southeast wall of the crater. I'd never known what well developed sex-lives elephants lead until I ran across this guy. I'd never thought about it, I guess. This guy had some kind of anatomical action going, he could even use his piece to scratch his belly. Wow!

I’d Never Thought About the Sex Life of Elephants.

We drove to the shallow-looking lake which floors a big portion of the crater (perhaps 30%). There were flamingos by the hundreds. It was just starting to rain, the scattered afternoon showers that seemed to occur every afternoon in the crater. Of course, this was when our vehicle started making ‘broken’ noises. Jonas stopped the Land Rover and opened the hood. He poked around inside the engine before shrugging his shoulders and starting it up again. Everything seemed to be fine. We drove out of the crater, since it was almost 4, by way of another hairy, steep, no-guard-rail road. There are two roads into the crater, one for going down, and one for going up. Some hotshot or bigwig decided he was going down into the crater for an afterhours visit, by means of the "up" road. Fortunately, at the corner where we met up with him, we could see him coming, so neither car was forced over the precipice.

Flamingos in the Rain.

We dropped off our Official Ngorongoro Crater Guide and drove on that afternoon toward the great Serengeti Plains and Ndutu Game Lodge. On the way we passed by a herd of galloping zebras and a number of giraffes.

Zebras.

The Serengeti

We drove for a couple of hours, descending from the hills west of Ngorongoro onto the great flat plain of the Serengeti. On the way, we passed by the turn-off which led several miles to Olduvai Gorge. We would visit Olduvai in a couple of days, so we didn't stop.

More Bookends.

The plain seemed endless, as did the animal life. Everywhere there were grazing herds of wildebeest, zebras, and gazelles. Occasionally, we'd see a jackal or hyena slinking through the grass or taking a nap. We drove for a while alongside a galloping infinitude of wildebeest. There were zillions of them in a rough line, ten to twenty animals deep, all galloping southward. The line extended as far as we could see to both the north and south. They were making their great annual migration. We'd heard that the migrations had passed Seronera (the nicest and most central of Serengeti game lodges) already, so there weren't many animals there. So we'd decided to go initially to Ndutu Game Lodge. Reports said there was plenty of game there.

Giraffe.

Off in the distance, perhaps twenty or thirty miles away, a classic cumulonimbus cloud was developing majestically. It was a dramatic backdrop for the endless running wildebeest.

Cumulonimbus.

We got to Ndutu just before sunset. The evening colors highlighted the spectacular cumulonimbus cloud which had continued to develop, miles to our west.

Cumulonimbus Later.

This had been our first full day of riding in the Land Rover and we were sore and tired. I felt as though I'd experienced enough rattling, bumping, bouncing, and jostling to last a lifetime. We went and sat in the screened-in porch next to the dining room and had our Safari Lager. On the cocktail table in front of us was a well-used copy of Hugo van Lawick's Savage Paradise. He's a famous African wildlife photographer who used to be married to Jane Goodall, the primate researcher. Savage Paradise is a collection of breathtaking photographs of Serengeti wildlife. Apparently, Ndutu is where van Lawick spent most of his time in the Serengeti. Great black-and-white enlargements of his photographs filled the walls of the bar and dining room there.

Our Safari Vehicle on the Serengeti Plain.

The next morning we headed north toward Naabi Gate. This is the official eastern entrance to the Serengeti Park. It's situated on a hill, which, although it is only fifty or sixty feet high, is visible for tens of miles because the plain is so flat.

Lions.

We entered the park and stopped when an oncoming Land Rover stopped us to tell us there was a group of lions right next to the road a few miles ahead. Sure enough, right beside the road was a group of six or eight healthy, happening lions. We were delighted. The pictures we took of these lions demonstrate that often the subject makes the picture; with lions like these as subjects, even the worst photographer would get dramatic photographs. At one point there was an altercation among the lions. One stepped on another's tail or something and there was a standoff. One of the contestants then moved off about thirty feet and lay down. So it wasn't anything serious, but it did provide us with some prize action shots.

Altercation Among the Lions.

Pleased with our capture, we returned to Ndutu for lunch. We'd decided we wanted to take a walk in the brush, instead of staying in the Land Rover. The manager of the hotel was alarmed at the suggestion, when we asked him where was a good place to walk around, he tried hard to discourage us. Only when we agreed to let someone from the lodge staff act as a "guide" did he become more helpful. We arranged that we would set out at four o'clock. Meanwhile we went out in the Land Rover for a couple of hours in search of game close to Ndutu. We found a number of giraffes, but not much else.

We Spotted a Hyena By Lake Masak.

At four, we met our guide and set off for a walk along the shore of Lake Masak. Our "guide" seemed to be a miscellaneous member of the kitchen staff who spoke little English and had little interest or knowledge about local animal life. His instructions seemed to have been: "Go along with these guys and make sure they stay out of trouble." We had a pleasant walk, but didn't see many animals. We came across a hyena taking a bath in the lake, and we saw some birds and a herd of gazelles, but that was about it. In any case, it was a welcome change from the physical assault of riding in the Land Rover.

Olduvai Gorge

The next morning we left Ndutu bound for Olduvai Gorge. We stopped several times along the way to look at jackals, hyenas, and vultures devouring the remains of wildebeest and gazelle carcasses, which were likely left over from the nocturnal predations of the night before. There seemed to be distinct "pecking orders" to the feeding process. A sole jackal scrounging meat from a carcass turned frequently to scare back the vultures which were eagerly advancing on the feast. We saw a carcass being picked over by the big ugly birds. One or two of the biggest were feeding and would chase away the others when they got too close. We came upon a couple of hyenas pawing a carcass. While we were watching, they seemed to decide they'd had enough. They walked away from the scene, leaving the remaining shreds of wildebeest to the birds, who set upon them eagerly.

Pecking Order. Hyenas Eat Before the Vultures.

I’ve Had Enough Lunch. I Think I’ll Go for a Walk.

If There’s a Jackal, He Eats Before the Vultures.

Olduvai Gorge is out in the middle of nowhere. There's a thatched-roofed platform where one can look into the gorge. Supposedly in the view are a number of the Leakeys' most significant archeological digs. But nothing is visible to indicate it. All the inactive digs have been cleaned up and all the active digs are out of sight of the viewpoint.

Olduvai Gorge.

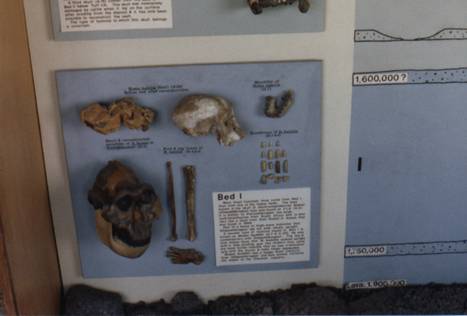

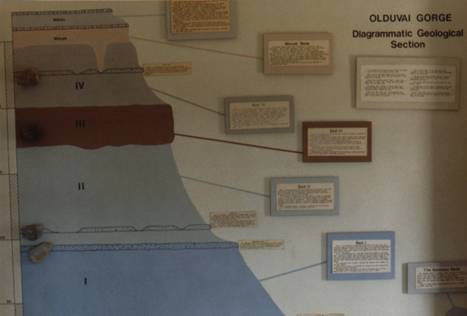

Next to the viewpoint is a small two-room museum. It's obvious that it was masterminded and funded by National Geographic. The diagrams and exhibits look like they are straight from the pages of the magazine.

Olduvai Gorge Museum Displays.

I was pleased to be able to buy Olduvai Gorge postcards there. My favorite is a portrait of Australopithecus. It's signed M.D. Leakey, as if it's an autographed posthumous self-portrait. There were a number of native Masai people standing around at the museum. I tried to take some pictures of them, but they all ran and hid behind the building. Even in this zone of National Geographic civilization, the superstition apparently remains that if one takes your picture they get your soul.

After leaving Olduvai Gorge, we started up into the hills surrounding Ngorongoro Crater. We came across a couple of Masai children. We gave them a few shillings and they were delighted to let us take pictures of them.

A Masai Child.

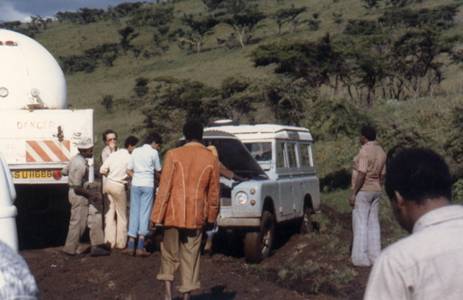

Travel Adventures

It started to rain, hard. The rutted dirt road became a sea of mud. The Land Rover was having a hard time making progress up the muddy hill, so Bob and I got out to push. We noticed the right front wheel wasn't turning. It seems that the bearings or other shpringenwerk on the wheel hub had gone blooey. Jonas turned off the engine, and without really talking to us about strategy, took the keys and walked away up the road. Presumably he was going to get help, and presumably he expected us to stay and wait for him, but he didn't say anything to us, and it was unclear whether we were to expect his return in hours, days, months, or years.

Our Chariot Sat, Hobbled, Beside the Muddy Road.

Bob and I sat there, soaking wet, in the middle of Africa, in a dead vehicle, waiting for the future. For some reason it struck us as funny, and we laughed for quite a while. Then we finished up the pulverized remains of the chocolate chip cookies Bob's mother had sent with us two weeks before for Kilimanjaro.

Soon another car came along. It was too filled up with people and gear for us to get a ride. Two men got out and we described our situation. They seemed to think we should get our disabled vehicle all the way off the road. Jonas had taken the keys with him, and the right front wheel wouldn't turn anyway, but we agreed that we probably should. One of them said something about the cheesy ignition systems in Land Rovers and produced a keyring full of keys which he began forcing into the ignition keyhole. We were incredulous when he started the engine. He said it was a key from his office file cabinet that did it. He drove the car backwards off the road in spite of the best efforts of the locked wheel to prevent movement. The two men got back in their vehicle and drove away.

They didn't get far. A couple of hundred yards up the road there were two gas trucks. They were stopped in a position where they effectively blocked the road. They weren't stuck, but they were stopped, "waiting for the road to improve". It was unclear exactly what this meant; whether they were waiting for it to dry out, or get rebuilt, we never found out. In any case, they refused to budge. The people who had moved our Land Rover off the road tried to drive around the gas trucks and promptly got stuck, in such a position that now the road was completely blocked.

Roadway Blockage.

Meanwhile, a couple of hundred yards back down the road, Bob and I had negotiated with a succeeding vehicle to get a ride to Lake Manyara, which was to have been our next destination. We piled our possessions and wedged our bodies in this Land Rover on top of the gear belonging to the family of German tourists who populated the car. We didn't talk much, but smiled a lot. We rode up the road the short distance to where it was blocked by gas trucks and the stuck vehicle.

The stuck vehicle was positioned with its front wheels spinning in air in ruts and its universal joint was resting on a hump in the road. The hump prevented sufficient weight from resting on the wheels to provide any traction. During the ensuing hour, cars began to accumulate on each side of the blockage. The thunderstorm which had precipitated the situation had retreated into the distance and left behind a pleasant sunny afternoon. Everyone got out of their various vehicles and milled about, socializing and making suggestions to the two or three people who were actively trying to extricate the stuck vehicle.

Eventually, the car was freed from the mire. A couple of other cars managed to pass over the difficult spot, including the Land Rover in which we had secured a ride. The fourth vehicle to attempt passage got to the exact spot where the first car had gotten stuck when suddenly the engine stopped. I don't know if it had run out of gas, or what the problem was, but the road was again blocked. We had to get into the Land Rover to take our ride, so I never saw whether all the remaining conveyances got their chance to pass the fated spot.

A mile or so down the road, we spotted a Land Rover full of people coming in our direction. One of the passengers was our driver, Jonas. We stopped and Jonas spoke with the driver of the car we were riding in. I thought they were confirming the arrangement that we would go on to Lake Manyara and wait for Jonas there. I was glad that the arrangement was now explicit and that we had reconnected with our AWOL driver and guide.

We rode the several remaining miles to Ngorongoro Crater Lodge. Here, to our surprise, the driver informed us that this is where we were to get off. I regarded this as a logistical mistake, but was unable to convince the driver to take us on to Lake Manyara. I was seized with a terrible crankiness which persisted for hours, much to Bob's discomfort.

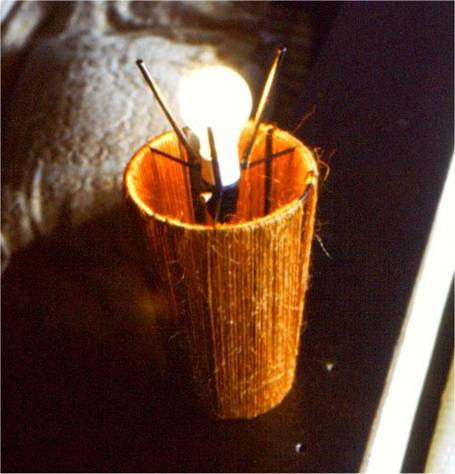

We checked into a room, and found that, as usual, of all the lamps and light fixtures in the room, only two worked, one in the bathroom and one in the room proper. I managed to vent some of my frustration on a nonfunctional table lamp. I took it apart. It worked once I reassembled it, but the bulb now protruded upward between the now-upward-pointing legs of the lamp. We never got a bill from the hotel for damage to the light fixture. Perhaps I should have billed them for fixing it.

I ‘Fixed’ the Lamp.

Ngorongoro Crater Lodge still did not serve Safari Lager, or any other beer for that matter, so Bob and I sat in the Lounge and tried some Dodoma Red, Tanzanian domestic wine. It was tolerable, but undistinguished. We each enjoyed wildebeest steaks for dinner. While we sat, we were shocked to be greeted by Jonas, who informed us that we would go to Lake Manyara in the morning. How? The Land Rover was outside. He'd fixed it? Yup. We were astonished. I'll never understand how he managed, in the middle of the Tanzanian wilderness, to get parts and tools to fix the wheel assembly of the Land Rover. Apparently, he'd once worked at the Crater Lodge, or as a crater tour guide, or something, and still had a lot of friends in the area. We felt very fortunate, all of a sudden, that we'd lucked into Jonas as our driver. He was forgiven for walking away earlier, leaving us in the mud with a dead Land Rover, without talking to us.

Lake Manyara

The next morning, we left for Lake Manyara. We stopped along the way, at every place that looked like it might have some gasoline. We were even directed off the road to a building where, Jonas was told, someone might have some set aside. No such luck. We went on to the Lake Manyara Hotel. It was about noon. The snooty desk people said there were no rooms ready for us to check into. So we managed to occupy ourselves at the swimming pool (rough life!).

Welcome to Lake Manyara National Park.

After lunch, we started to go down into Lake Manyara National Park. We didn't get out of the hotel before someone had asked Jonas to help them fix their VW bus. During the delay, Bob went back up to the room we'd finally checked into, and discovered, outside the window, a group of baboons wreaking havoc on the flower garden. He snapped a picture or two before the gardeners came and chased the baboons away.

Jonas was rewarded with a five-gallon can full of gasoline for his successful repair of the VW bus. We were all pleased. We set off for the park. The hotel sits atop the rift wall fault scarp. The park is at the base of the scarp. We stopped several times along the zigzag road down to try and photograph shy baboons, then we entered the park and drove around in search of animals.

Baboons in Lake

Manyara Park.

Baboons in Lake

Manyara Park.

We were hoping to find lions. Apparently, the Lake Manyara lions are famous as being the only lions who climb trees. They are reputed to climb to the lower branches of acacia trees where they are said to hang out. I couch this description in hypothetical terms because we never did see any lions in trees. That afternoon, we saw hippos and baboons, but no lions. Then we stopped at a little Indian souvenirs concession and stopped to buy some Masai beads and batiks for souvenirs. We went to back to the Lake Manyara Hotel and had dinner and played ping-pong. Heard an interesting story about obtaining black-market money from one of the British and German folks we sat with at dinner.

Plentiful Wildlife at Lake Manyara.

One of the Britons told this story. He was to go out and get into a taxi, which was followed by a Land Rover. He rode on in the taxi and the Land Rover disappeared. Then a different one appeared. He was driven to a scummy area of town with kids sitting in the streets and a malodorous perfusion of the environment. He was driven to where he was gotten out and introduced to an empty room with two mattresses on the floor and three deadbolts on the door. He was instructed to ‘make himself at home’. In a few moments, a person, who seemed like he might be from India or that part of the world, came in and proceeded to raise his pant leg and produce wads of bills. At many points our friend thought, “Now I’m a goner, for sure.” But it all worked out. Notably, unlike the way we obtained our ‘black market’ currency, he ended up with exchange receipts, with the carbon copies recycled back into the system, so even if checked, the transactions would seem legit.

Elephants.

The Baboon Snuck Up Behind a Giraffe to Post a ‘Kick Me’ Sign on Its Bum.

On Sunday, we got up and had breakfast and then left to Lake Manyara Park. We invited the two Britons to come with us on our second trip to the park and promised them reliable (sic) transportation to Arusha. They had ridden with their driver, a smooth talking slick sort, who had sold some of their petrol. Then he ran out of gas kilometers short of the main road west of Mikayune. They’d left him and hitched a ride back to Lake Manyara. They wanted to end up in Arusha, where we were headed after the park.

We drove around and saw some warthogs and no lions in trees, but we ran out of gas just when we saw some lions in the bushes and on the ground.

Lion at Lake Manyara.

Another Lion.

Jonas put in the 5 gallons of gas and we took a few pictures of the lions and then drove to Mosquito Creek where I bought some more beads and Bob won 40 shillings playing dice. We had a dry bag lunch as we drove.

At about 3:30 in the afternoon, we ran out of gas 30 km west of Arusha. Immediately, a bus came by, so we all got on it. We were surprised to see Jonas get off at the first stop. We rode to Arusha and took a cab to the hotel. Enjoyed a couple of beers in the garden. Jonas showed up and we gave him the gas can and thanked him for an adventure-filled safari. We took a cab to the Hotel 77 for dinner with the two British then came back to our hotel and went to sleep.

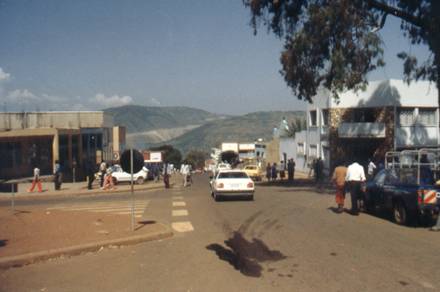

Arusha to Kigali to Gisenyi

The next morning, Monday, I paid for our room while Bob thanked Bushtrekker tours for the excellent service we’d received from Jonas, our Safari guide and driver. I believe we tipped Jonas, but I don’t recall the details. We got in a cab for 400 shillings to the airport but then the driver, en route, said he would charge us 500 - and he didn’t have enough gas anyway, so he took his back to the hotel. We were late already. We caught a different cab to Arusha Airport. We got onto the plane whose route included Mwanza Bujumbura and Kigali. We got off at Kigali and shared a cab with some friendly folks to the Hotel Meridien where we ate the lunch buffet and enjoyed a beer. Went outside and had a brief swim and some sun then took the shuttle bus to town center and walked around Kigali, the capital of Rwanda.

Part of the Crater Wall of Ngorongoro Crater.

En Route to Kigali, We Flew Over Ngorongoro. The Same Portion of the Crater Wall Was Visible.

Went back to the hotel enjoy dinner and went to sleep. The next morning we took the bus to town to the Air Rwanda office and we organized and arranged for the next few days of adventures. We walked to the Zaire embassy to drop off our visa applications, then we walked around town some more.

Kigali.

As we walked through Kigali, we stopped in at the hotel the ‘Hotel du 5 Juillet’, thinking that it might be cheaper than $50-per-double-per-night we were paying at the Meridien. We walked through the open gate, onto the grounds and into what looked like the office. After conversation in Bob’s broken French, we left embarrassed and amused. It turned out that ‘hotel’ also means residence or emplacement. We had walked into the mansion of the President of the Republic of Rwanda and asked how much a room was.

Hotel du 5 Juillet.

We caught the shuttle back to the Meridien. Had dinner and slept.

Up Wednesday. We saw the rental car that we had arranged drive up outside. It was some kind of small Suzuki jeep-equivalent with a sticky accelerator and only-uncomfortable seat position options. We drove to the Zaire embassy to pick up our visas which had been promised for 9 a.m., but the authority said it would be the next day or possibly at 4 p.m.. We went and found some snacks as breakfast and discussed things. Then we went back to the Zaire embassy and picked up our passports without visas. We went to the Burundi embassy for visas.

Akagera National Park, Rwanda

We drove out of Kigali and Bob drove us to Gabiro, where we checked in at the Gabiro Guest House. We had some lunch and then left for Akagera National Park. This game park is off the beaten track and was pretty informal and undeveloped. We did not see the abundance of wildlife we had encountered at Ngorongoro, the Serengeti, and Lake Manyara, but we did see some monkeys and I snapped a lovely photo of two gazelles.

Monkey.

Two Gazelles.

Appreciating Akagera Park was not without its complexities. This area was overabundantly endowed with tsetse flies, which are like large houseflies, but they bite. We were getting eaten alive by these wretched insects. In desperation, we rolled up the windows to seal them out, but it was already hot, and the little Suzuki, which had no air conditioning, immediately became an oven. It may have been a welcome switch for the wildlife, who usually provide the visual entertainment. I imagine this time we were the visually entertaining animals - as we desperately swatted at the bugs and rolled the windows up and down – all while trying to maintain the presence of mind to view our surroundings.

Another Gazelle.

We drove through the park and took a few wildlife photos then we came back and did laundry and I took my pictures of myself smoking next to a hideous lamp. We weren’t impressed by our dinner: a very tough chewy zebra steak.

Smoking Beside a Hideous Lamp

Looking North from Akagera Park Toward the Source Waters of the Nile.